“Hey buddy, can you spare some ventilators?” No, this is not an attempt at dark humor. This is the preamble of numerous calls that are going on across the nation right now. Whether the call is made to a ventilator manufacturer or to other medical centers, hospitals are busy stocking up on the highly technical devices that are anticipated to be in short supply. Here in North Carolina, where we’re still bracing for the coming wave of infections, our hospital managed to get a few extra to keep on hand in anticipation of future needs. When supplies like ventilators are anticipated to be in short supply, health systems like ours go out and try to buy a bunch of them. In essence, we are not unlike the hoards of people out there buying up toilet paper and hand sanitizer. A neighboring hospital was not so lucky, they only have a few spare ventilators. What’s worse, they’re in a larger city and are expected to be hit harder than we are. So when they asked us for a few ventilators, we obliged. That decision was not made without some trepidation. What if we end up needing them more than they do? Will they give them back? This crisis has turned hospital procurement into an art form. We’re all wheeler dealers now, often relying on the good will of our neighbors.

This highlights a problem with the approach taken by our disjointed health systems. Our hospitals are meant to take care of the patients in their own communities, it’s not their job to take care of patients in the next city or state, nor are they very good at thinking about those kinds of things. Yet this pandemic has made plain the problem with this piecemeal approach. Pandemics require a different type of thinking; we need to think about health care not in community terms but in terms that extend to our borders and beyond.

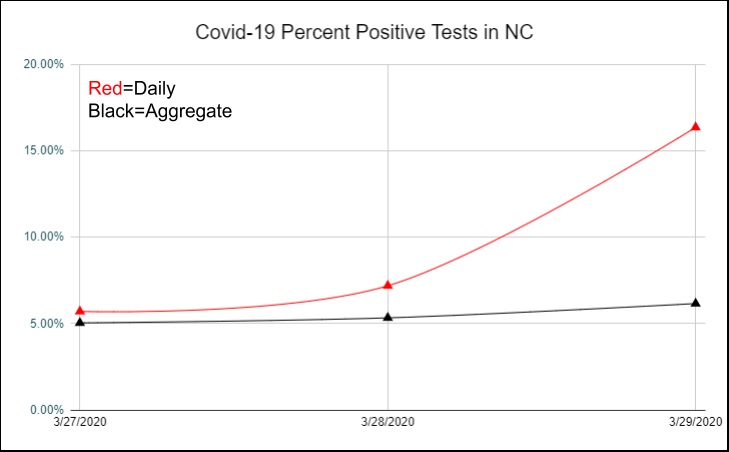

It is (poorly) estimated that there are maybe 160,000 ventilators in the U.S, with another 12,700 in the national stockpile. Estimates are that 960,000 people would require a ventilator. We doctors are not known for our math skills but even I can see that those numbers don’t seem to be working in our favor. With large swaths of the US population either practicing social distancing or being under shelter-in-place orders, we can be hopeful that the curve of infection will be considerably flattened. Remember the main purpose of flattening the curve is to reduce the rate of spread, not to prevent the spread indefinitely. So even with strict social distancing measures, we can expect that a large segment of the population, and by some estimates the majority, will still be infected by Covid-19 at some point. Social distancing only buys your local health system time to get ready for your inevitable arrival and for scientists to develop vaccines and treatments before that happens.

Does it buy us time to make more ventilators? Here’s the thing about vents. These are highly technical devices with sophisticated software and highly specialized hardware. You can’t just put them on a manufacturing line and strap them together quickly enough and in the volumes we need to solve the ventilator shortage. Many of the specialized bits are only made in a few places, and bottle necks will likely slow production. Even if we were to pump out ventilators at the rate of 100,000 per month just for our country, a number that seems unlikely, it would take a good 8 to 10 months before we had every ICU fully stocked up with the number of ventilators that they would need. Is that soon enough? In a word, no. At least not soon enough for the United States. Here, in the U.S. we’re already starting to ride up the steep part of the curve, that same curve that we’re trying to flatten. However even with all our efforts and with some flattening of the curve, the virus is going to cause a large surge of infections expected to overwhelm health systems over the next 1-2 months. There are parts of the world that will be desperate for vents in 8 months including the U.S. But that does not help all the people that will need them in the next 2 months, many of them will have perished by then.

So no, Ford, GM, and Chrysler will not be breathing for you any time soon. And honestly, do you really want a Ford Ventilator? Have you driven a Ford lately?

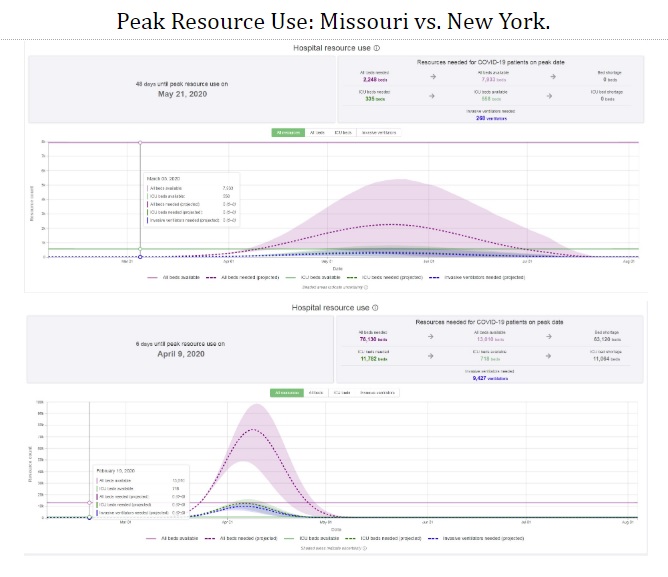

However, we do have one very important thing working in our favor that’s not relayed when you look at numbers about ventilator projections. That’s that the virus moves from region to region. So while a million or so people might in fact need a ventilator, they will not all need them at the same time. If we keep working at social distancing, we can turn this tsunami of disease into a steady rushing river that runs itself dry over a longer period of time. That rush will occur at different times in different places. As New York begins to calm down in a few weeks, other areas (like mine) are going to flare up. Viewed through that lens, the absolute number of ventilators is not the problem, the problem is that the ventilators that we have are inefficiently distributed.

The best short term solution to this problem, in addition to ramping up ventilator production, is to move the ventilators we have to where they are needed like a perverse national game of whack-a-mole. Ventilators, people and other ICU supplies have to be moved very quickly around the country. Normally we would rely on an organization like FEMA to manage this, but they’re good at managing one disaster in one area. In this situation they are clearly outmatched. Now I’m no military person, but I know enough to know that the U.S. military is the only organization with the command and control know-how and ability to manage a highly fluid situation like this in real time. Any army Major has more supply line ability in their little finger than a room fool of the smartest doctors and hospital administrators. The U.S. military is adept, experienced and professional. From Haiti to Djibouti there’s hardly a part of this planet that they haven’t conducted some sort of humanitarian mission.

This is a task that the U.S. military is uniquely qualified for. They are the organization that is best and most qualified to handle it and frankly are the only organization in the world that I would trust with a matter of this magnitude. Our present system places our hopes for salvation in the charity of businesses, kindness of fellow citizens and the zeal of competing health systems struggling to care for their communities. It is a system that is clearly failing. It is a system that is costing lives. The solution to our problem sits under our nose. It’s time to unlock the tremendous talent, knowledge, and logistical abilities of history’s greatest military.

Deep Ramachandran, M.D. is a Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep Medicine physician, founding CHEST Journal Social Media Editor, and co-Chair of ACCP Social Media Work Group. He blogs at Caduceusblog. He is on twitter @Caduceusblogger.