-by Matthew Moeller M.D.

I am writing this letter because I feel that our leaders and lawmakers do not have an accurate picture of what it actually entails to become a physician today; specifically, the financial, intellectual, social, mental, and physical demands of the profession. This is an opinion that is shared amongst many of my colleagues. Because of these concerns, I would like to personally relate my own story. My story discusses what it took to mold, educate, and train a young Midwestern boy from modest roots to become an outstanding physician, who is capable of taking care of any medical issues that may plague your own family, friends, or colleagues.

I grew up in the suburbs of southeast Michigan in a middle class family. My father is an engineer at General Motors and my mother is a Catholic school administrator in my hometown. My family worked hard and sacrificed much to enroll me in a private Catholic elementary school in a small town in Michigan. I thought I wanted to be a doctor in 5th grade based on my love of science and the idea of wanting to help others despite no extended family members involved in medicine. Winning a science fair project about the circulatory system in 6th grade really piqued my interest in the field. Throughout high school, I took several science courses that again reinforced my interest and enthusiasm towards the field of medicine. I then enrolled at Saint Louis University to advance my training for a total of eight years of intense education, including undergraduate and medical school. The goal was to prepare myself to take care of sick patients and to save the lives of others (four years of undergraduate premedical studies and four years of medical school). After graduation from medical school at age 26, I then pursued training in Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan, which was a three year program where I learned to manage complex problems associated with internal organs, including the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys and others. I then went on to pursue an additional 3 years of specialty medical training (fellowship) in the field of gastroenterology. The completion of that program culminated 14 years of post-high school education. It was as that point, at the tender age of 32 and searching for my first job, that I could say that my career in medicine began.

Over that 14 year time period of training, I, and many others like me, made tremendous sacrifices. Only now as I sit with my laptop in the dead of night, with the sounds of my children sleeping, can I look back and see where my journey began.

For me, it began in college, taking rigorous pre-medical courses against a large yearly burden of tuition: $27,000 of debt yearly for 4 years. I was one of the fortunate ones. Because I excelled in a competitive academic environment in high school and was able to maintain a position in the top tier of my class, I obtained an academic scholarship, covering 70% of this tuition. I was fortunate to have graduated from college with “only” $25,000 in student debt. Two weeks after finishing my undergraduate education, I began medical school. After including books, various exams that would typically cost $1000-$3000 per test, and medical school tuition, my yearly education costs amounted to $45,000 per year. Unlike most other fields of study, the demands of medical school education, with daytime classes and night time studying, make it nearly impossible to hold down an extra source of income. I spent an additional $5000 in my final year for application fees and interview travel as I sought a residency position in Internal Medicine. After being “matched” into a residency position in Michigan, I took out yet another $10,000 loan to relocate and pay for my final expenses in medical school, as moving expenses are not paid for by training programs.

At that point, with medical school completed, I was only halfway through my journey to becoming a doctor. I recall a moment then, sitting with a group of students in a room with a financial adviser who was saying something about how to consolidate loans. I stared meekly at numbers on a piece of paper listing what I owed for the 2 degrees that I had earned , knowing full well that I didn’t yet have the ability to earn a dime. I didn’t know whether to cry at the number or be happy that mine was lower than most of my friends. My number was $196,000. Continue reading “An Open Letter to Washington, D.C. From a Physician on the Front Lines.”

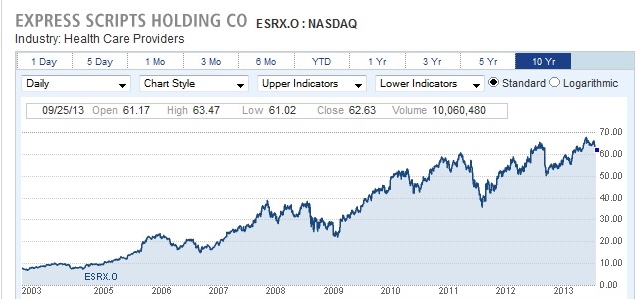

Continue reading “Why I Stopped Working with Express Scripts”

Continue reading “Why I Stopped Working with Express Scripts”