–Deep Ramachandran, M.D.

I grew up in a small town in the gently rolling hills of Connecticut. Previously unheard of, but now infamous, my hometown, Newtown, was a sleepy small New England town of mostly white people for whom my lone brown face served as diversity. I went to college at a mostly white college in said state, and went on to an Indian Medical School with predominantly other brown people. So you might imagine that July 1st, 2001 proved to be quite a shock. That was the day when I started my residency in Detroit, Michigan. Only I didn’t think there would be much culture shock, after all I was great guy who gets along with everybody. I was smart too, so naturally all patients would bow to my obvious mastery of medicine. It’s true that I had never really spent much time around African Americans, however I was an avid fan of both the Cosby show AND Fresh Prince of Bel Air. So really, what could go wrong?

Over the past 2 decades I’ve learned alot about how African Americans view health care and physicians. This is particularly important for anyone in the field of critical care where clinicians often need to discuss end of life care decisions with patients and their families. Many of these conversations revolve around changing the goals of care from cure to comfort. These conversations are difficult, emotionally charged, and put tremendous strain on patients and their families. They also put a strain on medical teams–it becomes demoralizing to continue to care for someone who is obviously suffering and has no real chance of getting better. These conversations can be even more frustrating with African American patients and families.

As someone who provides care to the African American community I can certainly endorse what the literature shows; African Americans are more likely to choose life sustaining therapies over palliative or hospice approaches. The literature also suggests that African Americans have less awareness of hospice and advance care planning, and are less likely to enroll in hospice. They are also more likely to withdraw from hospice to seek further life sustaining medical care. This is problematic as African Americans often have a greater illness burden at baseline, often have less access to medical care, and thus may have a greater need for palliative care services. Continue reading “African Americans Are Less Accepting of Hospice and Palliative Care at End of Life; What Can ICU Doctors Do?”

The Impact study showed that inhaled steroids reduced the incidence of COPD exacerbation, in contrast to previous studies which suggested that LABA/LAMA combinations (Anoro, Stiolto, Bevespi) reduced exacerbations similar or greater degree. However the study’s findings are not without controversy. Should you prescribe a triple inhaler (Trelegy), or stick with dual LABA/LAMA, or dual LAMA/ICS like Breo, advair? I discuss these issues in our first Pulmonary, Critical Care (PulmCC) Podcast and how Trelegy might fit into the treatment of people with COPD.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

May lay in a hospital bed, her wrinkled and mottled skin covered with leads, and sensors that monitored her every breath and heartbeat. A camera that was mounted on the wall allowed a doctor to zoom in closely enough to count her tattered eyelashes. Her husband sat at her bedside, gently stroking her withering gray hair as her chest moved slowly up and down accompanied by the soft whoosh-whoosh of the ventilator that breathed for her. He stared expectantly at her face as if at any moment she would rise and free herself from the myriad tubes that sustained her. Her adult daughters sat and stared blankly at the floor, waiting for something, anything. The streams of data transmitted from her body were monitored closely both by a team in a remote electronic-ICU bunker 50 miles away and her ICU nurse 15 feet away. Yet what May could not have realized was that despite her family’s presence at her bedside and the twenty-four hour care she received, she had been abandoned. She was alone.

Several weeks earlier, May came to the hospital from her nursing home, “yet another pneumonia”, the note in her chart said. “She seems to get one of these every few months” said her husband “can’t we give her something for that?”. The Emergency Room physician explained that she had aspiration, essentially choking on her own food and spit. She would continue to get pneumonia, until she eventually passed away. This wasn’t the first time he had heard this. “They told me before to let her die, but I didn’t listen to them, I told them to treat her anyway, and she made it through. I didn’t give up on her then and I’m not going to now”, adding “she’s a fighter”. Her husband Daniels countenance was such that the Emergency physician admitting May to the hospital didn’t bother asking whether his wife should be resuscitated in the event her heart or lungs stopped working and she needed to be put on life support. May was admitted to the general medical ward, and was started on antibiotics, but she eventually got worse. Sometime in the middle of the night a nurse found her ashen and struggling to breathe, and called a “code blue”. May’s breathing had gotten so bad that she needed life support, she had a tube put down her trachea and was taken to the ICU where she was put on a ventilator.

Doctors worked on her for more than a week, treating her pneumonia with powerful antibiotics. But even as her pneumonia cleared, her body withered. Her skin hung from her bones as her muscles wasted away, her eyes hollowed, and the skin of her arms filled with bruises as nurses struggled to find a place from which to draw blood. On the second Sunday of her ICU stay, the doctors tried a “trial extubation”. As the family understood it, her lungs had improved to the point that she might be able to be taken off the ventilator, but her body was now so weak, they did not know whether she would actually be able to breathe on her own. If she had to be put back on the ventilator, the doctors told them, she would require a tracheostomy that would allow her to live on the ventilator long term. The social worker would then seek placement in a long term facility for patients on long term ventilators, essentially a hybrid hospital, rehab, and nursing home in one. Her breathing failed within minutes of being taken off the ventilator, and she was immediately put back on life support.

It was the following day, Monday morning, that I met with May’s family to discuss what had happened the day before, it was the beginning of my ICU week. For May and her family it was the beginning of their third week in the ICU, and it showed. Her husband, Daniel looked unkept, his thick shock of gray hair was whirled and tangled, his flannel shirt partly tucked into ripped and stained jeans. He gave the impression of someone who had not been taking care of himself, let alone someone who could take care of his chronically ill wife. His visage upon seeing me betrayed both surprise and regret as he recognized me from four months earlier. I was the doctor who told him that May was going to die. Continue reading “Not Dead but Not Alive; The terminally unhealed languish in America’s hospitals.”

Study Shows That Bariatric Surgery Reduced COPD Exacerbations by More Than Half

I often tell my patients with COPD that quitting smoking can have a greater effect on their respiratory health than any inhaler that I could prescribe them. Should I now also extend that advice to include weight loss for obese patients with COPD? In this journal CHEST® study, researchers used registry data to look at COPD exacerbations for patients both before and after bariatric surgery. In the year before bariatric surgery, risk of COPD exacerbations was 31%. Looking at the rate of COPD exacerbations during the year after bariatric surgery, that rate dropped to 12%, an astounding change.

The accompanying editorial proposes mechanisms explaining why this might be so and postulates whether obesity could be a modifiable risk factor in COPD. While these results are certainly exciting, we look forward to future investigation into whether bariatric surgery, or other weight loss means, could further help reduce risk of COPD exacerbation.

Pneumonia: If You Can’t See It, Does It Still Exist?

The diagnosis of pneumonia requires the radiographic presence of infiltrates on imaging. However, with its greater resolution, CT scanning can often demonstrate infiltrates when none are seen on chest roentgenogram. Do we treat these the same as a regular pneumonia? This study sought to quantify differences between patients with pneumonia as seen on a chest radiograph vs CT scanning. The differences between the two groups appeared to be minor, with procalcitonin levels appearing to be lower in the CT group. Otherwise, it would appear that patients with pneumonia seen only on CT scanning should be managed like other groups.

The accompanying editorial raises the question of what to do with patients who are suspected of pneumonia but have negative chest radiographs. Certainly, exposing them all to CT scanning can’t be the right answer. Perhaps we should err on the side of caution and treat these patients for pneumonia when clinical suspicion is high. Conversely, we should consider CT scanning in this group only if suspicion is low and the presence of an infiltrate would change management. Continue reading “Pulmonary Medicine Update: Bariatric surgery for COPD exacerbations & The Mortality Indicator that Won’t Die.”

Hospitals run short of critical medications after loss of production in Puerto Rico facilities.

“Doc, you mind switching that to an oral preparation?”, our clinical pharmacist inquired during multi-disciplinary rounds as intravenous infusion devices beeped annoyingly in the background. Taking care of ICU patients can be extraordinarily complicated, so doing it as part of a team helps make sure that all bases are covered. ICU’s like ours have a BEEP BEEP BEEP. Excuse me, for a moment, Staci, can you get that thing to stop, please? BEEP, BEEP, BEE– Thanks, Staci!. As I was saying, like many hospitals, ours uses a multidisciplinary model which makes rounds on all patients in the ICU. An ICU nurse, clinical pharmacist, dietitian, social worker, pastoral care, respiratory therapist, each provides important insight and perspective that guides patient care in the right direction.

As a pulmonary, critical care doc, I’m lucky to have a great team, so my ears perked up when I heard the suggestion. This was now the third patient he had made a suggestion to switch a medication to the oral route from the intravenous route. “What gives, Scott?” Over the past few years, we’ve been experiencing alot of spot medication shortages either because of inadequate supply, or because of precipitous price increases; we can usually change to an alternative. But today was different. Today we were switching a number of different medications, all of which were intravenous to oral formulations of the same or similar medicines.

“It’s not the medicines,” he replied, “It’s the bags they’re in”. Continue reading “Devastation in Puerto Rico leads to hospital shortages in U.S.”

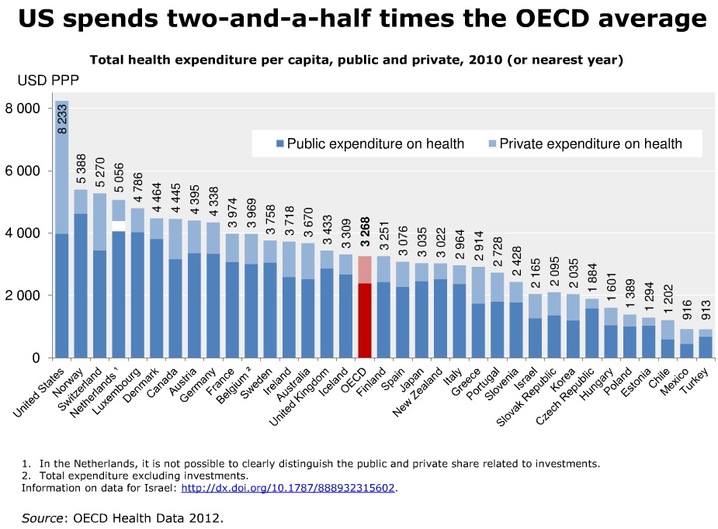

Republicans have been waiting a long time for this moment. They have tried, time and again, (and again and again!) to repeal Obamacare. Now at long last, after sixty previous attempts to overturn the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as Obamacare, their moment has arrived. Continue reading “7 Reasons Why President Trump Can’t Repeal Obamacare.”

Recently I read an article in the NY Times by Elisabeth Rosenthal. She’s the same author of the enlightening article “My doctor charged me $117,000 and all I got was this lousy hospital gown” That may not have been the exact title of the article. Continue reading “Why Doctors Don’t Like to Send You Test Results.”

Like a lot of people, I get pretty numbed to gun violence on television. I stopped watching the local news because all they seem to show is news about shootings. The general public’s perception about gun violence is that it’s always somebody else, that the person who was shot had somehow been involved in crime. The numbness we feel to gun violence often ends for most of us when things hit close to home, when you or someone you know is affected. Continue reading “Doctors’ Prescription to Reduce Gun Violence”

I enjoy fielding questions from patients. Yes, I sense you’re rolling your eyes, but really, anything that I can answer that helps keep them out of the hospital is, I feel, time well spent. Recently though, I’ve been fielding a number of questions that have me concerned. These questions often have a leading tenor about them like, “are you using stem cells for COPD yet?” The questions imply that stem cells are the de rigeur treatment for COPD. Now I may not be at the leading edge of any fashion, but being unfashionable in my treatment regimens? Never!

I can’t blame anyone for wanting to seek out treatments for COPD. It is after all, a leading cause of death and illness in the U.S. And it’s widely regarded that the changes caused by COPD/emphysema in the lungs are permanent. While there are now several different treatment options for emphysema/COPD, very few can prolong life. So if I had a family member with emphysema, I might naturally seek out treatments for COPD that go beyond the usual treatments, and with all the hype surrounding stem cells, why not take a look?

What people find when they google “stem cells and COPD” is in a word, distressing. It’s a fantasy world full of promises of health, healing, and better breathing. Equally distressing are the things that people who visit these sites aren’t recognizing: the greed, lies, lack of ethics, illusions, and misleading claims. Continue reading “Stem Cells and COPD: What You Need to Know.”